Holding ownership in foreign non-Canadian entities can create significant adverse Canadian tax consequences for the unwary. Ownership in a foreign entity is not as uncommon as one may initially think. For example, it can often be the result of ownership before immigrating to Canada, an inheritance, investing in a non-Canadian start-up company, or simply as a means for holding income generating real estate in a foreign jurisdiction. On its surface, investing in or through a foreign entity may seem to have benefits – the foreign jurisdiction may have no tax, or at least a tax rate that is lower than Canada; or perhaps there are beneficial ownership privacy laws which the Canadian resident investor wishes to take advantage of. Regardless of a Canadian resident taxpayer’s motivation, the benefits of investing in a foreign entity could be partially or completely offset by Canadian tax laws designed to discourage ownership structures which try to take advantage of earning passive investment income in a low or no tax jurisdiction.

The main mitigating set of rules designed to eliminate the tax advantages from investing outside of Canada is the foreign accrual property income (“FAPI”) regime. These rules are aimed at curtailing earning property income (i.e.: rents, royalties, interest, and dividends) in a foreign jurisdiction where a Canadian resident taxpayer controls the foreign entity earning the income. When considering whether a taxpayer controls a non-Canadian entity, the test is purposely broad. A foreign entity is considered a “controlled foreign affiliate” if a Canadian resident taxpayer controls the entity. For these purposes, a Canadian taxpayer is deemed to own not only the shares they own directly, but also any shares owned by:

a) Persons who do not deal at arm’s length with the taxpayer (i.e.: family members);

b) Up to four arm’s length Canadian resident shareholders; and

c) All persons who do not deal at arm’s length with the persons in b).

The FAPI regime mandates the immediate taxation in Canada on property income earned abroad by a controlled foreign affiliate if it is not repatriated to Canada in the same taxation year. Any taxes paid by the foreign entity can reduce the FAPI income inclusion by a factor of 1.9 for individuals and 4 for corporations, although the 2022 Federal Budget proposes to reduce the gross up factor to 1.9 for corporations for taxation years beginning after April 6, 2022. As such, for Canadian individual (and moving forward, corporate) shareholders, any potential FAPI inclusion would net out to nil so long as the foreign entity pays a tax rate of no less than 52.63 per cent on its property income in the home jurisdiction. In addition, any property losses (otherwise known as foreign accrual property losses (“FAPL”)) realized in any of the preceding 20 years may be used to offset the current year’s FAPI. There is also no FAPI inclusion for a Canadian taxpayer if the FAPI of the foreign entity is less than $5,000 in a taxation year. To the extent there is a FAPI inclusion, the amount reported by the taxpayer is added to the cost base of the shares of the foreign entity for that shareholder.

Generally, arm’s length business income earned outside of Canada would not fall into the FAPI regime. This is consistent with the objective of the FAPI rules, namely to mitigate any tax advantage from earning passive investment income through a controlled entity in a foreign jurisdiction. That being said, the FAPI rules are extremely complex and there are situations where business income earned by a controlled foreign affiliate could be recharacterized into FAPI.

Let’s look at an example of how the FAPI regime is intended to apply:

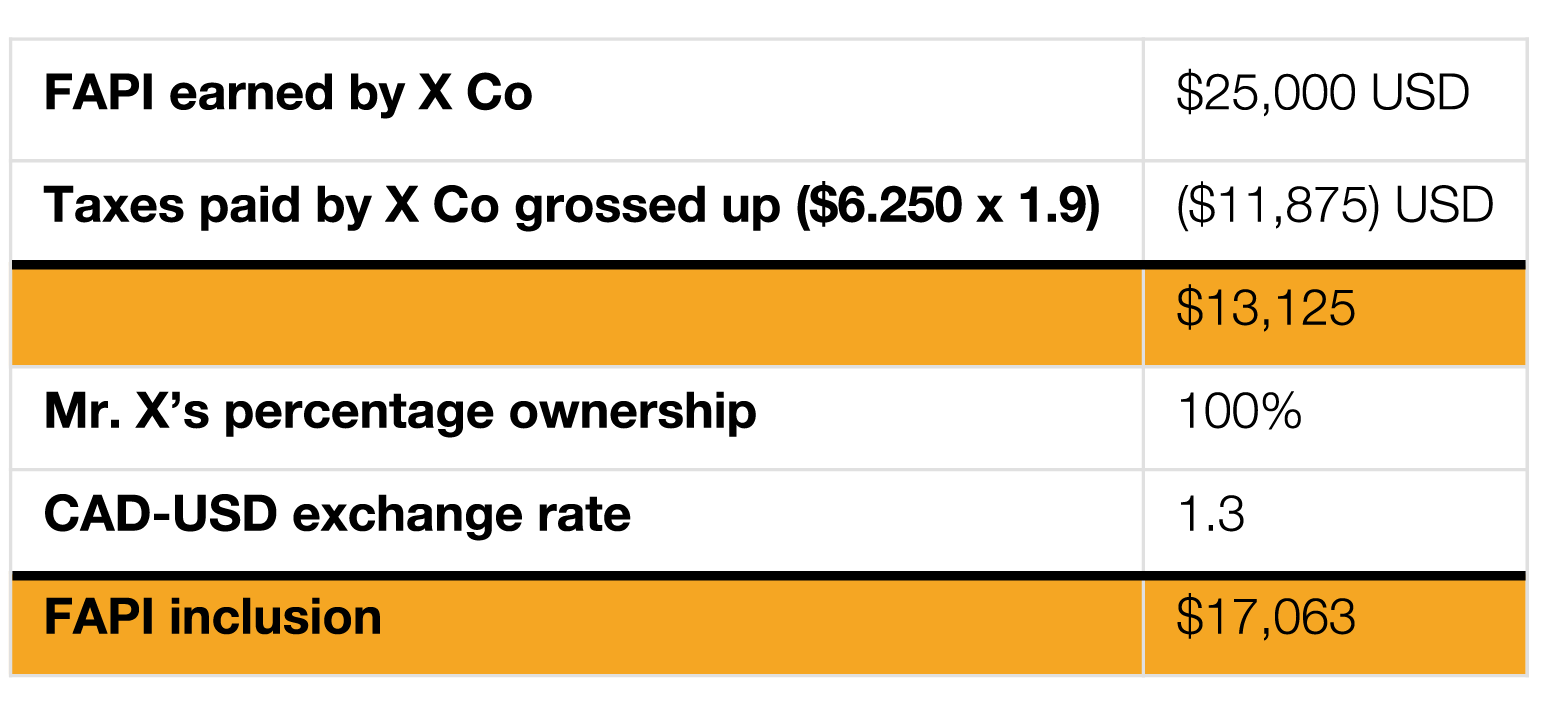

Mr. X is the sole shareholder of a corporation, X Co. X Co is resident in the United States, it has no employees and holds a piece of real estate which it rents out at a net profit of $25,000 USD annually. X Co pays taxes at a 25 per cent tax rate in the United States. The Canadian-US dollar exchange rate is 1.3 to 1.

Since Mr. X is the sole shareholder, he controls X Co and X Co is considered a controlled foreign affiliate. X Co’s income is passive investment income and therefore is subject to the FAPI rules. The FAPI inclusion for Mr. X would be as follows:

The FAPI regime can unsuspectingly cause Canadian tax for Canadian resident shareholders of controlled foreign entities. The issues and rules can be far more complicated than what has been described in this article and, in most cases, require expert professional advice. If these circumstances apply to you, please contact a member of the Crowe Soberman LLP Tax Group.

This article has been prepared for the general information of our clients. Please note that this publication should not be considered a substitute for personalized advice related to your situation.